[OPINION] Law weaponized for injustice in Talaingod

The conviction of the Talaingod 13, affirmed by the Court of Appeals, stands as a stark illustration of how the law can be turned from a shield into a weapon. This is not simply a criminal case. It is a story about indigenous education, militarization, and the shrinking space for compassion in the Philippines.

At the center of this story is the Lumad school in Talaingod, operated by Salugpongan Ta Tanu Igkanogon Community Learning Center Inc. The school arose because the State failed to provide accessible education to remote indigenous communities in Davao del Norte. With the consent of tribal elders and parents, it taught basic literacy and numeracy alongside Lumad culture, history, and sustainable agriculture. For many families, it was the only viable form of schooling that did not require children to abandon their language, land, and identity.

The Lumad schools

Lumad schools, more broadly, emerged across Mindanao as community-based responses to decades of State neglect. In many ancestral domains, public schools were either geographically unreachable, chronically under-resourced, or altogether absent. Lumad schools filled that vacuum. They were not substitutes for the public education system but expressions of the right of indigenous peoples to education that is culturally appropriate, community governed, and responsive to their lived realities.

These schools did more than teach reading and arithmetic. They preserved indigenous knowledge systems, histories, and ecological practices. They linked education to food security, environmental stewardship, and collective survival. For Lumad communities facing land-grabbing, extractive projects, and militarization, education was inseparable from the defense of land, culture, and life itself.

This model of education is not outside the law. It is affirmed by international norms to which the Philippines has freely committed itself.

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples recognizes the right of indigenous peoples to establish and control their educational systems and institutions, providing education in their own languages and in a manner appropriate to their cultural methods of teaching and learning.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child requires States to ensure that education develops respect for a child’s cultural identity, language, and values. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights affirms education as a right that must be accessible and adaptable to marginalized communities. These are not abstract ideals. They are binding commitments that should guide policy and judicial interpretation.

Displacement and the bakwit schools

Under the Duterte administration, Lumad schools became objects of suspicion and hostility. They were repeatedly accused of being fronts for the communist movement, often without credible evidence and without due process. Many were forcibly closed. Teachers were harassed, arrested, or threatened. Students were subjected to military presence and interrogation.

The Department of Education during this period was not a neutral bystander. Through school closures, denial or withdrawal of permits, and silence in the face of red-tagging and militarization, DepEd became complicit in the suppression of indigenous education rather than its protection.

As militarization intensified, Lumad families were forced to flee their communities. Children, teachers, and parents sought refuge in Davao City, Cebu, and Metro Manila. Out of this displacement emerged the Bakwit schools, including those hosted by the University of the Philippines and supported by churches and civil society.

The Bakwit schools were humanitarian responses to crisis. They provided temporary learning spaces so displaced Lumad children could continue their education while away from their ancestral lands. Faculty members, students, volunteers, church workers, and human rights advocates stepped in where the State had failed. These schools were not ideological projects, but emergency classrooms, grounded in child protection, dignity, and care.

A perverted prosecution

It was in this same context that the events leading to the Talaingod 13 case unfolded in 2018. As military operations intensified in Talaingod, Lumad families fled. Children, teachers, and community members sought refuge in Davao City with the assistance of church workers, educators, and human rights advocates. Rather than recognizing this as a humanitarian response to displacement, the State filed charges of child abuse against the humanitarian team and rescuers.

Those convicted include Satur Ocampo and France Castro, prominent activists and Makabayan legislators, Meggie Nolasco, executive director of the Lumad school in Talaingod, and her fellow Lumad teachers and humanitarian workers.

I know personally the legislators and the Lumad teachers involved, and I have nothing but admiration for them. They should be lauded for their humanitarian actions, not prosecuted.

The prosecution’s theory inverted reality. Children who had fled fear and insecurity were portrayed as kidnap victims. Parents who testified that their children left voluntarily were sidelined. The broader context of militarization, school closures, and official hostility to Lumad education was treated as irrelevant. Acts of care were reframed as crimes.

The Regional Trial Court in Tagum City convicted the accused, and the Court of Appeals affirmed that conviction. These outcomes are now part of the legal record. But legality does not always mean justice. Law can be applied in ways that are formally correct yet morally hollow, especially when cases are shaped by power, fear, and institutional bias. The law listened upward to security narratives rather than downward to indigenous experience, contrary to international standards that require the best interests of the child to be a primary consideration in all actions affecting children.

A call to the Department of Education

The deeper tragedy is that the Lumad school in Talaingod, the Bakwit schools, and the humanitarian efforts of the Talaingod 13 existed because the State failed these children. Instead of correcting that failure, the response was closure, criminalization, and punishment. Education was treated not as a right to be fulfilled but as a threat to be eliminated.

DepEd can and must choose a different path. With Secretary Sonny Angara now at its helm, DepEd has an opportunity to realign policy with constitutional and international obligations. This means recognizing community-based indigenous schools as legitimate expressions of the right to education, ending the practice of red-tagging educators and learners, and ensuring that militarization has no place in classrooms or learning spaces. It means developing clear protocols to protect displaced indigenous children and support emergency and transitional education, including Bakwit schools, in partnership with universities, churches, and communities.

Law should protect education, not criminalize it. It should shield the vulnerable, not weaponize fear against them. The Talaingod 13 case stands as a warning of what happens when education and law are guided by power rather than justice, and a challenge to today’s leaders to honor our legal commitments, listen to indigenous voices, and choose compassion over repression. – Rappler.com

You May Also Like

Sandbrook Capital Announces Acquisition of United Utility Services from Bernhard Capital Partners

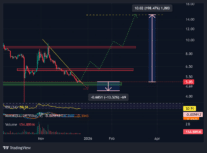

TRUMP Struggles Below $5 as Unlock Adds Downside Pressure